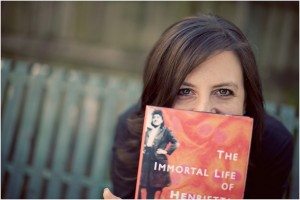

Nancy Chuda: it’s so great to talk to you and hear your voice. I’ve been following your trail and this is such an honor for us at LuxEco Living and for me personally to have the honor of talking to you today. Thank you so much! So you must be exhausted, but with that exhaustion comes the exuberance of life and the success that is now yours, and it’s so exciting.

Nancy Chuda: it’s so great to talk to you and hear your voice. I’ve been following your trail and this is such an honor for us at LuxEco Living and for me personally to have the honor of talking to you today. Thank you so much! So you must be exhausted, but with that exhaustion comes the exuberance of life and the success that is now yours, and it’s so exciting.

Rebecca Skloot: Yes, absolutely.

NC: Did you just get back from England? I thought I’d seen something on your Facebook site that you’d just gotten back.

RS: Yeah, I did. I was in the UK for about a week and I’ve been back for… I don’t even know how long!

NC:Oh wow! I guess it’s to our advantage that you’re kind of winding down a little bit now, and actually we’re winding up! So we’re very fortunate to have this opportunity to speak with you and to really come to understand the complexity of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, which is, in my opinion, one of the most important books of our century. And I just can’t congratulate you enough on the hard work and the endeavor that went into this. I picked up the book, and I’ll tell you, I was just explaining this to our staff here today, I was reading The Help by Kathryn Stockett. I put it down, and of course loved that book, and owning a Kindle, up pops “if you liked that, you’ll love this!”

RS: Oh that’s interesting

NC: And that’s how I discovered Henrietta was through The Help.

RS: That’s good!

NC: Well anyway, let’s plow ahead and we’ll begin

RS: Okay

NC: What I find so fascinating about you, Rebecca, is that science is your love and you began this quest at, was it 16 yrs of age? Is that when you first discovered Henrietta Lacks and the HeLa cells?

RS: Right, at 16, yeah.

NC: And at that time in your life, going back, that was a wake up call for you in so many ways that would obviously lead to this great work. If you can explain why the scientific findings of the HeLa cells is so important?

RS: They have been used for everything from the first polio vaccine; they went up on the first space mission to see the results of zero gravity. The number of scientific landmarks that have come from the cells just goes on and on to this day. There’s something like 5 Nobel prizes now that have been awarded for research that used her cells. The scientific importance of them you really can’t overstate. A lot of why they’re useful is that they’re sort of a workhorse. They’re useful for a lot of basic research. They’re sort of almost like the fruit fly or white lab mouse, they’re everywhere, they’re very cheap to grow and easy to grow, and they’re just a standard in a lot of labs all over the world

NC: For just a moment I’d like to reflect on Henrietta herself, and in 1951 her diagnosis and her entry to Johns Hopkins. What I found sort of disturbing was the fact that she was diagnosed with HPV, and obviously that she had contracted syphilis, which I guess was not uncommon. Is there some remorse, in terms of the family, and certainly in terms of, in a sense, her husband having in a way been the interceptor to causing the syphilis which may have, or probably did, lead to the disease

RS: Every once and a while people bring that up in “Q and A”s. I think some readers feel a lot of anger or have questions about that, but it’s one of those things that it’s hard to look at from an outside perspective. We don’t really know what happened within the family, we do know that he did bring home some STDs while she was sick, but who knows really where the STDs came from? There’s no way to know essentially what Henrietta was up to. If she had been with someone before, and there were rumors that maybe she had been with Crazy Joe, in the book, I mentioned that there were some rumors that they were together. So you really can’t know for sure. But regardless, placing blame, you know “he killed her by giving her the STDs” is tough to do because it was such a different time, it was a different culture, they didn’t have any idea about sexually transmitted diseases. And so I avoid doing that at all in the book intentionally, and let people have the reactions they’re going to have. A couple of their children went through a little phase where they were angry with him, that it was his doing. But really, that passed for them for the same reasons I’ve said. It was such a different time and you can’t know what happened exactly and that they didn’t know. So the family doesn’t really see it that way.

NC: Is the family, at this particular point in time, however, having gone through this process with you, I mean you were, to a certain extent, literally adopted by this family The story would never been told had they not embraced you. And part of the mountain that you had to climb, besides the tremendous amount of research and ten years of your life, which I commend more than anything, is how you were in a sense inducted into the Lacks family.

RS: Yeah, there was definitely a sort of hazing process. They now look back at that and sort of laugh. But, you know they were very wary of me, it took about a year and half for them to talk to me, and they had good reason to be wary. I didn’t know that at the time but I was one in a long line of people who had come to them, essentially wanting something from them and it hadn’t worked out in the past. So it took a lot of time to convince them that I was someone they could trust with the story, and I think it took a lot of courage on the part of Deborah, who really was the one who was most involved to get beyond the some of the things that had happened before, and say “no I really want to do this, I really want the story to get out there, and I want to learn myself what the story was.” A lot of it was that I’m a very persistent person. I’d felt since the beginning that this was such an important story to tell and I’d never really let go of that. And so it was a combination of that, and Deborah initially having the courage to hear me out, and then to come with me as I did my reporting. I never met anyone who was more determined to learn something than she was.

NC: I must tell you, Rebecca. The pivotal moment for me having read this book, aside from the incredible scientific accomplishments that have been yielded and will continue to yield, but for me, the personal, the intrapersonal moments in this book between you and Deborah are riveting. There are scenes in the story, in particular, in the motel room on the bed, and her going through her bipolar moments, and you literally having not slept, pulling out your hair, wondering, “Am I going to get this? Is it going to work? Am I crazy? Is she crazy?” And then, the quote, which sticks with me to this day,

“As her daughter Deborah once whispered to a vial of her cells, ‘you’re famous, just nobody knows it.’”

And she has children of her own, and they carry the genetic code. And what I find, again the sort of subplot of this story, are really these cells. And what happens to The Lack Line, if you will, and are there other Lacks cells that will be as generous as Henrietta’s and continue in the scientific brigade?

RS: No, there won’t. The cells that are growing are her cancer cells, not her normal cells, and her cancer was caused by the HPV, which is not something that is passed on from generation to generation. Her children, grandchildren, great grandchildren don’t have those cells. It was very particular to her and her cancer, so it won’t live on in future generations. But the DNA inside of her cells is her DNA and that does live on in all the future generations. They all have little bits of that DNA as well.

NC: Do you find it somewhat personally astounding that basically there are all of these scientific experiments with laboratory animals and Petri dishes, and lo and behold here come these cells in particular that are practically gyrating out of their own nucleus and creating more cells. In a way that is a sense of immortality, the fact that these cells continue to live on. Billions of dollars of research have been conducted with these cells. Do you find that there is a cause and effect type of relationship between these cells and Henrietta’s spirit and the scientific improvement that these cells are providing the planet?

RS: I think that’s up to everyone to decide for themselves. The cells are immortal, that’s the scientific term, “Immortal Cells.” So they are technically and scientifically immortal which means they’ll live on forever and never die and so a lot of people say, “does that mean she’s immortal?” And it really does depend on your definition of what life is and what it means to live on, and her DNA is a live inside of there, and so there is a part of her that is living on and growing and dividing and being a part of all of this incredibly important research. Her family believes that she was brought back to life in these cells, that it’s essentially a miracle, that she was chosen as an angel to be resurrected in these cells and to cure diseases and to take care of people. And that would be fitting to her personality in life; she was a big care taker, she had 5 kids when she died and she was this incredibly giving mother and all she wanted to do was take care of her kids. She was the same way with other people, if you lived near by and you were hungry you would go to her house and she would feed you, if you needed a place to stay and you didn’t have any money, you would sleep on her floor, if you needed a girlfriend she would find you one. She was just a caretaker, and so for her family, the personality of her cells is very much like her. So they really believe that’s her in there.

NC: There’s comfort in that for them I would imagine.

RS: Oh absolutely.

NC: There’s a resolution for them, but what I think the reader also comes away with after reading the story, you know again the subject of bioethics. The idea that, here’s a woman who, in 1951, enters a hospital and does not consent to tissue being taken from her body. Now this is not too different from today, and yet there’s a growing concern around the issue of bioethics and whether or not pharmaceutical companies, scientific research, all these things, should they be the beneficiaries of somebody else’s issue?

RS: Yeah, this is an issue that’s being debated and I think it will continue to be debated for a while. Some of these bigger questions, who owns biological materials, who should be profiting off of them, and what should be told to people when they’re taken to the hospital or the doctor and have routine tests and the samples are taken, because often those are used in research and people don’t realize it.

NC: The fact that it always comes back to what we’ve learned in the book and certainly from other supporting articles, and obviously many of the interviews you’ve conducted, is that money changes hands. Billions of dollars have changed hands off of HeLa, yet it sounds odd to say this, the family has not only been robbed of their inheritance to a certain degree, but they’ve also been robbed of the financial participation of this pool. Do you think that’s fair?

RS: I don’t think it’s my job as a journalist to say, “what is fair, what is not?” I feel like my job in all of this is to put the story out there and to let people decide for themselves what to think. Because it really is a complicated issue, there are a lot of different sides to it! One of my goals for the book was to explore all of the different sides of the story and show the family’s story and what they’ve been through, how they struggle now, show all the good that’s come from the cells and also the scientists and their stories. It’s not any easy question to answer, “Where was wrong done in all this?” And to look back at the 1950s, you can’t look using the eyes of today and what we know. Informed consent didn’t even really exist then and it was absolutely standard practice for people to take tissue and try to grow them and culture them, that sort of thing, the various other things that happened in the future: the commercialization of the cells, her medical records that were released to the press and published, her children used in research without their knowledge, that gets progressively more and more ethically questionable as you go along because that wasn’t standard practice later in the story. So in a lot of ways, the moment the cells were taken is the least controversial moment when it comes to ethics in terms of the way things were done. So I really do feel like it’s a story to put out there and have people decide for themselves. But then of course I hear again and again as I travel around and talk about the book, it often comes back to this one thing. So much money was made off of this woman’s cells, so much incredible finance, in some way everyone has benefited from these cells except her family, who have in some ways suffered because of them. Here they are, they can’t afford to go to the doctor. That’s a disparity that’s often very hard for people to reconcile. When you talk about using tissues in research, scientists and biotech companies, and various people involved say, “Everyone benefits from this type of research.” Which is true, which is partially true anyway. The science that comes out of this research is so incredibly important but the reality of things in the United States right now is that not everyone does benefit, because not everyone has access to health care.

NC: That’s true.

RS: So in some ways, this is part of the larger health care debate. The people who are the source of some of the raw materials, those materials are made into products, which are then sold back to the people and often those people cannot afford them.

NC: I’d like to switch gears just for a little bit here and focus on you. In the actual research, which obviously, as you mentioned, took you ten years and the various drafts, there were critical times in which decisions were made that were not productive in terms of what you ultimately have provided, and then there came that catapult moment through 2 other influencing sources that made you realize that you had to be in this book. That must have been for you, as a writer and a researcher, an almost scary place to arrive at, but at the same time an exciting juncture.

RS: Well, I wouldn’t describe it as exciting… It wasn’t a decision that I made lightly. It was something that I really resisted for a long time. I think that often times writers insert themselves into stories where they really don’t belong. It’s sometimes hard to resist that because it’s easier in some ways to write in the first person, and I actually found it much harder. So, yeah, there were a lot of reasons why I didn’t feel I should be in the book. Their story didn’t seem like a place where I belonged. But then I eventually realized I had become a character in their story. It wasn’t that I was inserting myself onto their story but I was in it.

NC: Well, it makes sense to me, Rebecca. I have a science background, I don’t have a degree, but I served on NIH’s council for five years as founder of my charity, and having gone through, gosh, years and years of science and rounds and deciding which university and which doctor is going to get a research grant for a substantial amount of millions of dollars. You know, you listen to the science and it gets pretty boring, and for the layperson, the average person, they don’t even understand the language. So in my opinion if you had not inserted yourself into the story, it may not have been a New York Times Bestseller.

RS: Yeah, I’ve certainly heard that. And you know this is one of the things, I teach writing, and I talk to students about when a writer should be in the story and when they shouldn’t. I often say the two times you should be is when you are an actual character, if you are part of the story, or if you serve as a necessary bridge to something very foreign to them. You can be a translator. Sometimes a first person account can give readers someone to relate to, to really feel like it’s their guide to the story. There are definitely people out there where my presence served as that. But I also really feel it’s more so the narrative arc of the quest, I actually view it as Deborah’s quest, not so much mine, to learn more about her mother and to come to terms with it all, which she does through us travelling together. Which I think helps readers to connect to the story in a way that they might not if it were just a science story. I mean obviously the human story, on so many different levels is what allows people to care about the science and to really understand how it relates to their everyday lives and why it’s important.

NC: Sure, and you know, on that note, because so much work went into this in editing and revising. I don’t think most people who Kindle and buy books at Borders, or listen to authors on wonderful television shows, really understand the process. They pay the dollars, buy the book, celebrate the reading, and share with friends but they don’t understand the agony and the ecstasy. Can you share some of that with us? The agony of the writing and the ecstasy of knowing you’re a New York Times Bestseller.

RS: I really don’t know any writers who the writing process is easy for. It is a very difficult thing to do. For me, I struggled a lot just on the very basic, nuts and bolts level, trying to figure out the structure of the book. It’s an incredibly complicated structure, it took a really long time to try and figure out how to map it out, make it work. It involved reading a lot of novels, watching a bunch of movies. So just that on a nuts and bolts level took probably over a year.

NC: Wow!

R: But you’re working on a lot of different things at once. The process of creating the structure is ongoing. Throughout the 10 years I was working on the book I was constantly working on the structure in some way. It’s an emotional event.

NC: Oh I can’t imagine!

RS: For me some of the things that were particularly intense were the emotions in the book. The suffering that’s in the book. When I wrote the scene of Henrietta’s death, and really, she did not die a very peaceful death, it was pretty painful for her. And writing that was incredibly difficult to do. I wrote the first draft in one sitting where I basically didn’t move from my chair for 10 hours. I revised it and revised it and revised it and then I couldn’t really move. I just went and sort of lay down for several days. And couldn’t really do anything. I was just devastated by it, because when you recreate the story like that you really experience it in way, so you experience the emotions of it. There was so much pain and suffering involved, it drains you in a way. I’ve heard other writers that write about war or anything traumatic have that same sort of experience.

NC: During that time, I’m interested to know, as you mentioned that it was so emotionally draining, and yet it was something you knew you had to write, you had to go through the pain to get to the passion so to speak, did you ever get sick, personally? Did you ever find that you couldn’t go back to your desk, that you had to take a break?

RS: Oh yeah, after writing that… There was a decent stretch of days, it probably wasn’t a whole week, but it was close to it. I just couldn’t do anything. I would just sort of lie there, it was as if I was physically recovering from it.

NC: But then, when the book finally launched… Let’s jump to the icing! When the book finally launched and it jettisoned up to the New York Times Bestsellers list, and all of the press, and there you are after ten years of mining this story, and expounding on this incredible life of Henrietta and the science. When did you actually know that it was going to become a bestseller?

RS: Well you never can know until it actually is! I knew it had the potential to be, in part because what I see people reacting to in the book, you know readers, I think what drove it to the bestsellers list is the story. It’s the fact of the story. The reaction I see people having is exactly the reaction I had when I first heard the story, which is, “Oh my god, I have to tell people about this! I have to know more about this. People should know about this.” I knew that just because of the way the story grabbed me, I knew it had the potential to grab everyone else as well. So for me the big task as a writer was to essentially stay out of the way of the story and to put it together in a way that it let it deliver that impact to people, to let it grab people. I knew it had the potential, but whether it would succeed at that…and once the book was done, you just never know. The publishing industry is, something of a mess in some ways right now. You know, there are so many wonderful books out there that some people spend decades of their lives working on and then they come out and they don’t get any press or they disappear for one reason or another because they were published on the same day as some other book. A lot of that doesn’t have anything to do with the book. There are so many different factors. And I knew a lot of that, so you can only hope that it will work.

NC: And it did!

RS: It was an enormous relief that it did make it out there because it means people were reading it, and the story is getting out there.

NC: What I find fascinating, Rebecca, when you think about molecular cellular biology, the idea is that Henrietta’s cytoplasm, it’s just this whole concept of, what is a cell? And when you think about the underlying takeaway, the hub of the book, which are HeLa cells, what they produced and what they continue to produce, and you think about the book becoming a critical mass and affecting the critical mass, almost like a virus itself, it’s interesting to me, I see this as a very symbolic gesture for your success.

RS: You know it’s funny, there are quite a few people who have pointed out to me that the book is growing like HeLa cells, which is of course alright with me.

NC: It is! And then the piece de resistance, and I can celebrate a little bit with you because OprahWinfrey covered the greenhouse when my husband James Chuda built and designed it, and to have Oprah Winfrey come to your door and say everybody in America needs to see this, I mean, I know what the “O Experience” is like personally, and now to know that the “O Experience” is now going to be in your life with Henrietta, perpetuating even more the opportunity of getting more people to read the book, see the movie, you must be on cloud nine! I can’t even imagine as an author knowing that your book is going to an HBO movie of the week.

RS: Yeah I’m thrilled about that. I’m thrilled about Oprah being involved, and Alan Ball, the other producer is just great. I’m just ecstatic about that, and so is the family!

NC: Oh, they must be ecstatic! Can you share with us, if you can, if you can’t we understand. Has there been any discussion about casting?

RS: Not yet! We informally, the family and I, we definitely have spent time imagining who would play who. But there hasn’t been any official discussion Right now we’re looking for a screen play writer, so that comes first.

NC: You know who comes to my mind? I don’t know, maybe it’s the physical resemblance of QueenLatifah as a young Henrietta?

RS: Yeah, she’s definitely come up a few times!

NC: No, really! Let’s talk about her physicality! Her bone structure, you know, Henrietta had these glorious high cheekbones, she was a beautiful woman! Queen Latifah has that very same big-boned, I’m here for now… If you asked me, I’d consider her!

RS: Definitely, from very early on the family thought she could be in it. It will be really fun to see what happens.

NC: Talk about a hayride! Aside from the great success you’re experiencing, with the book, and now it’s being made into a movie, it’s like the ten years you dug in and delivered this masterpiece, in many ways, what I’m feeling and sensing is that Henrietta is coming back and this is her gift to you, Rebecca. This is her gift, to you.

RS: Thank you. There have certainly been members of the family that say “you know, she’s guiding the book around!”