by Zhenya Gershman

Rembrandt is unquestionably one of the most famous and beloved artists of all time. His work has been scrutinized for centuries with fascinating books on just about every aspect of his career including such titles as: Rembrandt’s Nose, Rembrandt’s Eyes, Rembrandt’s Reading, Rembrandt and the Female Nude, Rembrandt’s Jews, and The Rembrandt House just to name a few. You’d think that we know everything about him. Yet, there are still many gray areas in our understanding of Rembrandt: his religious affiliation is uncertain, and titles and interpretations to his paintings were guesses attributed after his death. Many mistakes were made in the process. For example, the famous Night Watch turned out to be likely a day scene and the number of his paintings shrunk from over a thousand to a few hundred with the rest accredited to his students and followers. To make things worse, Rembrandt left no documentation about his art except for seven uneventful letters nudging to be paid for his commissions.

In my pursuit of unveiling Rembrandt’s mysteries, I turned directly to his art for “keys” and discovered a missing link in our understanding of his work. I was able to deduce that Rembrandt was a member of a secret fraternity, either an early Freemason or a Rosicrucian. This initial hunch was confirmed by countless facts visible in his paintings, drawings, and prints. Let’s reconsider the meaning and inspiration behind Rembrandt’s work using seven major clues.

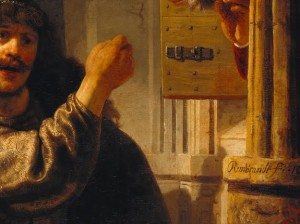

1. THE CODE OF A HIDDEN HAND

Follow Rembrandt’s gesture in his self-portrait from around 1636. His left hand is inserted into the lapel, prominent enough so that you can detect it. You will find an identical gesture in Masonic diagrams as well as in Peale’s portrait from 1776 of George Washington who was one of the greatly revered Masonic members. The hidden fingers represent an internal disposition of faith. This sign is saying to other initiates of the order: “This is what I’m part of, this is what I believe in and this is what I’m working for”. Malcolm C. Duncan, the great authority on Masonic Ritual describes: “How do you know that you are a Freemason?”—“By signs, words and touches”. Rembrandt is clearly communicating with the viewer as he stares right out of the portrait. Is the hiding of the hand in Rembrandt’s self-portrait actually a way of revealing an important message?

2. THE MESSAGE OF LIGHT AND DARK

Imagine a painting by Rembrandt—most likely the first thing that comes to mind is the dramatic contrast of light and dark known as Chiaroscuro. What lies beneath this impetus to create illuminated figures that emerge from darkness?

Light is of major importance in the science of Masonic symbolism. It represents Divine Truth lighting the path of life’s pilgrimage. Without darkness one cannot be enlightened. One has to precede the other, as night precedes morning. No wonder Goethe, a genius writer and a Freemason, is believed to have uttered the following words before dying: Mehr Licht (more light). Not coincidentally, Rembrandt was one of Goethe’s favorite artists. Goethe purchased Rembrandt’s remarkable etching The Alchemist to be strategically placed on his 1790 first edition of Faust. Goethe’s famous line: “There is strong shadow where there is much light” reflects this particular Masonic concept and is often represented in black and white checkered floors in Masonic images and ceremonies. It is clear that Rembrandt was not merely interested in perfecting a painting formula, but was participating in the esoteric tradition of exploring the symbolism of light and dark.

3.THE TRUTH BEHIND THE NAME

Let’s look at an amazing and never before explained fact: Rembrandt’s birth name was Rembrant without a “d”. In all signatures after 1633 Rembrandt insisted on adding the “d” to his name, while in most written documents he is mentioned as Rembrant without this addition. This was part of a gradual change in his identity reflected by his signature. In less than ten years Rembrandt reduced his signature to his first name only by dropping the customary reference to his family name (van Rijn), his father’s name (using the letter “H” standing for Herman) and the city of birth (using the letter “L” to refer to Leiden). He then added the mysterious “d” to his first name. What was the significance of this peculiar change considering his first name is pronounced identically either way? In addition he began to emphasize the letter “b” in his name by either capitalizing it right in the middle of his name or clearly separating his signature to two parts Rem Brandt.

Let’s look at an amazing and never before explained fact: Rembrandt’s birth name was Rembrant without a “d”. In all signatures after 1633 Rembrandt insisted on adding the “d” to his name, while in most written documents he is mentioned as Rembrant without this addition. This was part of a gradual change in his identity reflected by his signature. In less than ten years Rembrandt reduced his signature to his first name only by dropping the customary reference to his family name (van Rijn), his father’s name (using the letter “H” standing for Herman) and the city of birth (using the letter “L” to refer to Leiden). He then added the mysterious “d” to his first name. What was the significance of this peculiar change considering his first name is pronounced identically either way? In addition he began to emphasize the letter “b” in his name by either capitalizing it right in the middle of his name or clearly separating his signature to two parts Rem Brandt.

An old Dutch dictionary revealed to me the meaning of these two words. The definitions were stunning: brandt means light and rem stands for clog or dim. Thus the artist changed his name to Rembrandt to signify a combination of two opposites, a direct reference to his trademark chiaroscuro. Consequently, was the self-imposed “d” in his first name changing it to mean the extremes of light and dark, a fraternity hint for the initiated?

4. THE THREE SECRET DOTS

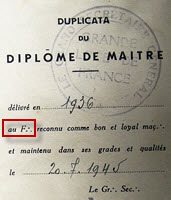

Curiously, Rembrandt repeatedly added a beautifully rendered letter “f” after signing his name. Scholars have attributed this to implying “fecit” or “made by”. A master of multiple meanings, Rembrandt would have enjoyed the potential of this letter to also evoke the word frater (brother). Thus his signature would be read as Rembrandt, fraternally implying his belonging to a closed fraternal society.

In addition Rembrandt added three dots following the letter “f”. This seemingly minor gesture is of major importance. Albert C. Mackey in his Encyclopedia of Freemasonry recorded: “Abbreviations of technical terms or of official titles are of very extensive use in Freemasonry… a Masonic abbreviation is distinguished by three points,.:, in a triangular form following the letter.” It was a form of coded communication in signaling Freemasons to other Brothers. Mackey goes through the list of known abbreviations in which “f” stands proudly for Brother as we have suspected. Compare a close up of Rembrandt’s signature to a document from Grande Lodge of France: you will see the letter “f” followed by triangular arrangement of three dots. Jacques Huyghebaert in Three Points in Masonic Context specifies that these three dots “also appeared in signatures, which explains why Freemasons are still called in French: ‘Les Frères Trois Points (The Three Point Brothers)”. A great number of Rembrandt’s signatures display the exact same three dots proudly, a type of public display that remained invisible to the uninitiated.

5. ETCHED IN STONE:

Rembrandt is always creative with every detail including the placement of his signature. His signatures go beyond the basic purpose of claiming authorship. Additionally, they serve as accents or direct the viewer to the artist’s intent. Rembrandt consistently added his name on stone surfaces as you can observe at the base of a column in his painting Samson Threatening his Father-in-law.

In Masonic ritual and legend, stone (as one might expect) plays a leading role. Beginning with the new apprentice, who is entrusted with polishing the rough stone with hammer and chisel, and culminating in the variously shaped stones appearing in the Master Mason Degree, there is hardly a ceremony in freemasonry that is not connected in some way with stone. It is noteworthy that after completion of the initiation ceremony, the new Brother is placed in a particular position within the Lodge and is usually told that he represents the cornerstone on which freemasonry’s spiritual Temple must be built. Additionally, when joining Royal Arch Masonry, the initiated is asked to create a signature “mark” which serves as a personal identifier carved into stone. On numerous occasions, Rembrandt places the signature in his paintings as if written on stone.

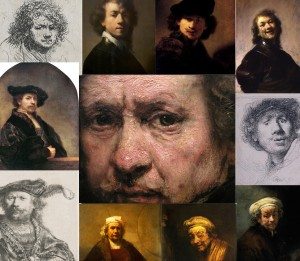

6. THE STUDY OF THE SELF

Rembrandt’s extraordinary contribution to self-portraiture bears strong resemblance to the Masonic task of ongoing self-examination. Unlike most organized groups, Freemasons strive for the cultivation of individuality rather than adjusting to fit in with the preexistent structure. Each member’s task is to cultivate and “polish” oneself, a process akin to polishing a rough stone to smooth perfection. This undertaking involves not only striving for self-perfection and thus realizing full potential, but understanding one’s personal limitations. The concept of initiating change in the world by changing oneself is at the basis of the Masonic way of life. No wonder Masonic philosophy appealed to such great and independent minds as Benjamin Franklin, Haydn, Mozart, Schiller, Jonathan Swift, Voltaire, and Oscar Wilde. Few painters have practiced the task of scrupulous self-examination as much as did Rembrandt. In just four years, between 1627 and 1631, he portrayed himself at least 20 times. He painted, etched, and drew his own likeness at least 75 times over 40 years in an astonishing number of roles, ranging from a street beggar to the Apostle Paul. Just as in his preoccupation with light and dark, Rembrandt’s ongoing practice of self-portraiture is also akin to the Masonic philosophy of self-realization.

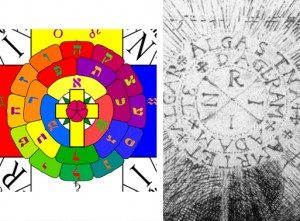

7. THE ALCHEMY OF A ROSICRUCIAN CROSS

In his famous print The Alchemist, Rembrandt presents us with a visual riddle in which the subject witnesses a mysterious radiating disk surrounded by three concentric circles appearing in mid-air. This apparition bears a secret inscription, which was de-coded by using a mirror and deciphering the Latin anagram to read as Hebrew words that spell the name of God. The middle of the roundel bears a cross dividing it into four sections with the letters INRI (Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum or Jesus Christ, King of the Jews). David Lyle Jeffrey suggested that this vision and inscription has particular significance for freemasonry. In addition to the Christian interpretation of the letters INRI signifying Christ, Jeffrey adds that for Masons this represents Igne Natura Renovatur Integra (the sacred fire of Masonry that naturally regenerates humankind). Furthermore, I suggest a new and illuminating juxtaposition: compare the Rosicrucian Cross (also prevalent in Masonic symbolism) to Rembrandt’s image of the vision. Here you will find all of the same ingredients: the three concentric circles, the cross in the middle, transliteration in Latin of Hebrew words spelling God, and the letters INRI.

A curious footnote to this riddle is that the letters have been rotated by Rembrandt with the “R” residing prominently at the top, spelling RIIN clockwise. Riin is an equivalent way to notate Rembrandt’s last name Rijn, since in Dutch the capital letters “I” and “J” can be written identically. Rembrandt thus added a clever and daring spin to the abbreviation of the letter “R” from Rex (or King), identifying himself by either first or last name: “R” for Rembrandt or “R” for “Rijn” and thus equating himself with God. Rembrandt once again embedded his presence in a secret signature that can be deciphered by the holders of the “keys”.

THE KEY TO THE DOOR

These seven clues are just the first chapter in a monumental study of Rembrandt’s involvement in esoteric circles. It is important to look at this discovery not as a conspiracy theory, but as applying the Rosicrucian-Masonic philosophy and rituals to help understand the work of the great “Master” and perhaps to create new possibilities to the significance and resonance of Rembrandt’s work in our lives today.

Anyone can visit Rembrandt’s house today. You do not need a special key to open the front door; just present a ticket to enter what is now a museum.

Another entry awaits one prepared to use the key that Rembrandt left us through his work—are we ready to open that door?

Article based on “Rembrandt: Turn of the Key”—for the complete story visit Arion, Boston University http://www.bu.edu/arion/latestissue/

ZHENYA GERSHMAN is a well-known artist, art historian and museum educator. Zhenya worked for over a decade in The J. Paul Getty Museum, bringing her passion and unique understanding of art to thousands of people. Her work is dedicated to uncovering new perspectives regarding the life and work of Rembrandt, and she has contributed to such exhibitions as Rembrandt’s Late Religious Portraits and Rembrandt: Telling the Difference. Zhenya has offered numerous workshops on Rembrandt’s painting, drawing, and printmaking techniques at various cultural institutions including the Hammer Museum. Her groundbreaking discovery regarding the presence of a hidden Rembrandt self portrait was published by Arion, Boston University and was brought to European audiences by Le Monde, one of the most important international magazines. She is a Co-Founder of Project Awe, dedicated to the study of Aesthetics of Western Esotericism. Between painting in her studio in Los Angeles, Zhenya is working on a book and TV series on Rembrandt. www.ZhenyaGershman.com