By Elizabeth Grossman, Author of Chasing Molecules: Poisonous Products, Human Health, and the Promise of Green Chemistry, High Tech Trash: Digital Devices, Hidden Toxics, and Human Health

By Elizabeth Grossman, Author of Chasing Molecules: Poisonous Products, Human Health, and the Promise of Green Chemistry, High Tech Trash: Digital Devices, Hidden Toxics, and Human Health

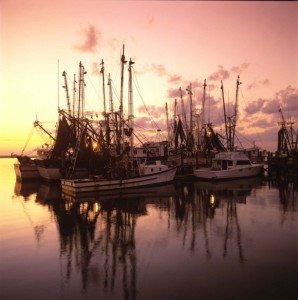

“This is the one thing that could destroy our culture and I don’t want to see it happen,” says Grand Isle, Louisiana resident Karen Hopkins, wiping at tears she’s clearly fighting. Hopkins, a Louisiana native and long-time resident of Grand Isle, runs the office at Dean Blanchard Seafood. Blanchard typically buys 13 to 15 million pounds of Gulf Coast shrimp annually. Hopkins’ house sits across from what should be a busy loading area for Dean Blanchard Seafood and no more than ten yards from a pier where boats that should be gearing up for a night out shrimping are coming in from a day skimming oil and changing oil-soaked boom.

It’s June 16th, in the midst of brown and inland shrimp season when Blanchard’s should be buying 400,000 to 500,000 pounds of shrimp a day. Most of the year’s catch comes in what’s typically a forty-five day season. The Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded just as the 2010 shrimp season was getting underway.

“Before the closures began, we took in about one-eighth, maybe one-tenth of what we should have,” Hopkins tells me. “But now we’re totally shut down. I should be working 80 to 120 hours a week this time of year,” she says. “But now I’m working on a no pay basis.”

In fact there’s so little work at Blanchard’s that Dean Blanchard, who’s a superstar in the Louisiana shrimp business – Louisiana provides most of the nation’s shrimp and roughly a quarter of the country’s commercial seafood – said when I stopped in, “I’m going in circles. I don’t know what to do with myself. I built all this over the last thirty years, and now for what?”

Grand Isle sits at the far southern end of the watery marshes and bayous that define Louisiana’s coast. Most houses are on stilts. There appears to be more water than land in this part of the state, and Louisiana’s fragile wetlands are eroding at a rate of 25 to 35 square miles a year. Water is front yard and back yard throughout bayou country, and working boats line the omnipresent waterfront. The roads down to the coast are lined with seafood shacks. Most sport handwritten signs advertising crabs, crawfish, and shrimp. Most are now closed.

In the summer swelter – the heat index hovers near 100ºF – the air shimmers against the pale blue sky and salt water that runs from steel gray to a Caribbean aqua. By noon huge cumulous clouds and thunderheads tower above the horizon. At dusk the insect hum is tropical. Between the fishing bayous, the dazzling green marshland is riddled with oil and gas fields. It’s not uncommon to see oil pipes and rig equipment rising beyond the shrimp nets.

Grand Isle was hit hard by Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Gustav. But the community, which island resident Jeannine Braud describes as “a family,” rebuilt. “You knew when that [disaster] was over. You’d wake up and hear hammers,” she says. But then came the financial meltdown and the bad weather winter of 2009 that kept tourists away. “This season was going to be the one that got us over the hump,” says Hopkins.

But coastal residents see no end to this disaster. “It’s not just shut off this year but for years and possibly generations to come,” says Hopkins of the fishing, shrimping, and shellfish harvests that sustain Gulf Coast communities.

“This is all I’ve ever wanted to do all my life,” one Grand Isle fisherman tells me. “My car’s paid off, my boat’s paid off, but I’ve got a house.” So he’s working for BP on the clean-up.

Hopkins describes a recent visit to friends who live further inland on one of the bayous. “We’d go up there for speckled trout and shrimp. When the fish came out at night there were so many shrimp it looked like the water was boiling. Now that’s gone. The shrimp are still there but we can’t go and get them,” she says, near tears. “We just sat out at the picnic table and cried.”

Add to these difficulties the language barrier faced by many in the Vietnamese-American Gulf Coast fishing community. “About one-third of the commercial fishing vessels in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi are owned by the Southeast Asian community,” says Kaitlin Truong, chair of the Biloxi-based organization Asian Americans for Change. “Eighty percent of our families and about one in five Vietnamese work in seafood,” she tells me, jobs that include employment in local seafood processing plants.

There’s the immediate financial collapse of the seafood industry to be dealt with, Truong explains. But what’s making it worse are the uncertainties, she says. Her words echo what I’ve heard from Grand Isle to Biloxi, Mississippi to Dauphin Island, Orange Beach, and Perdito Key, Alabama and into Florida. While the oil continues to gush from the sea floor, there is no end in sight. And nearly two months into this disaster the flow of information, while improved in some areas, is far from satisfactory.

If Karen Hopkins, who runs the office for a multi-million dollar business, is having trouble with the BP claims process, imagine how difficult it is for someone who doesn’t speak English. “I know the spill is bad but it is even worse when you don’t get us information,” is a common complaint, Kaitlin Truong tells me. “There’s a desperate need for information. A lot of these people don’t have computers,” she says, explaining that the Deepwater Horizon Response reliance on web-based communication is not reaching many people who need this information desperately.

Only a small fraction, perhaps ten percent, of Asian-Americans who’d signed up to work with the Vessels of Opportunity program (out-of-work commercial fishing boats being hired by BP for clean up) have been activated, Truong tells me. “All they want is an opportunity to work,” she says. “Some are concerned their house is going to be gone, their boat is going to be gone, and they’re worried about putting food on the table.”

The seasonal nature of the seafood business makes the fishing closures particularly hard to weather. Truoung explains that fishermen invest a lot prepping their boats for the season. Now they can’t earn that money back.

“Some contractors are hiring locals, but it’s hit or miss,” Tony Kennon, Mayor of Orange Beach, Alabama tells me.

Paul McIntyre, who fishes out of Buras, Louisiana says he signed up for offshore clean-up duty but isn’t sure he wants to run the health risks. “I don’t want my kid spending the next 20 years taking care of me,” he says. Instead he’s hoping to join a crew building berms.

“A lot of fisherman are scared and confused. They’re afraid their careers are probably coming to an end and they won’t be able to fish any more,” says Truong. For those who are older, training for another career is unlikely. “What about people my dad’s age who aren’t going to go back to school?”

“I don’t want to learn the oil field business. I don’t want to do barge rentals,” says Karen Hopkins.

There is anger and frustration now. But Truong is concerned about what she calls “post-oil anxiety and depression.” “We see it in some of our town hall meetings,” she says.

Hopkins and Braud are also concerned about the psychological – and social – toll the oil disaster is taking on their community. They tell me what life is like on the island where there are no stop lights and you don’t have to lock your door. The school year is ending and beach cabins should be filling with families. The island’s narrow roads should be filled with children riding bikes and buying sno-cones. Instead there are men in boots and safety vests. Heavy equipment and television news vans are parked outside vacation rental properties. The southern tip of the island, where clean-up staging takes place, is guarded by temporary chain-link fences and personnel from the West Jefferson Parish sheriff’s office.

In the Grand Isle Sureway supermarket a cashier shakes her head and glances at the mostly empty aisles. “This place should be filled with families buying groceries. Now we have single men,” she says. I get in line to pay for sunscreen and bottled water behind a soldier in fatigues and black lace-up boots buying chewing tobacco and snacks. Greenpeace is running a tab at the Bridgeside Marina, which is now stocking more hardware than tackle. News crews and clean-up contractors work their cell phones on the deck above the idled bait tanks.

Many of the beach cleanup crews are bussed in. The crew supervisors won’t speak to me, nor will the contractors’ offices I’ve contacted. Neither state nor federal agencies – nor BP – have yet told me where these workers are coming from. The rumor among locals is that these crews include ex-offenders. The influx of these outsiders and so many men without families in tow is creating community tensions. These come in addition to those stemming from loss of income, livelihoods, and quite possibly an entire way of life.

“We need grief counseling. And on an on-going basis,” says Hopkins who worries that the stress and depression will take a physical toll on island families. “This is the kind of thing that can destroy families and send people into addiction,” she says.

“I heard the same thing in Larose, Dulac, Golden Meadow, and Houma. This need seems to be foremost on people’s minds throughout the fishing communities,” says John Sullivan, co-director of the public forum and toxic assistance program at the University Texas Medical Branch NIEHS Center in Environmental Toxicology, who’s working with community groups on the Gulf Coast.

“They’ve destroyed our coastline. Raped our natural resources. They’ve portrayed us as drunks and people who don’t want to work,” says Hopkins. “But this couldn’t be farther from the truth. We’re very self-sufficient but this is totally out of our hands. We didn’t do anything wrong.”

Out on the water off Grand Isle, dozens of fishing and shrimp boats wield skimmers and tend to boom. The hard boom is rimmed black with oil. The absorbent boom looks like socks soaked in axle grease. Crews lean out over the water that swirls with the ruptured well effluent known as Louisiana light sweet crude. There are lumps, chunks, and whorls. It looks like sewage. Pelicans cruise by from their oil-fouled nesting ground. A pod of dolphins surfaces between two work boats towing skimmers.

“In our hearts, we know it’s over,” says Hopkins glancing toward the idled waterfront.

Reposted via The Pump Handle