by Zhenya Gershman, Artist and Art Historian, co-Founder of Project AWE

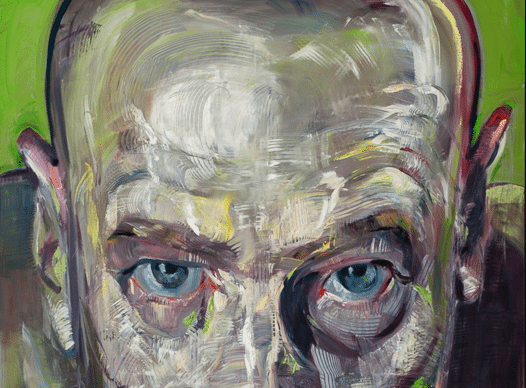

You are in an art museum. Suddenly you feel that someone is staring at you. You stop and turn around. There is no one in the room. But the feeling persists. You look around again and realize that an old portrait of an unknown man is staring at you. Yes – a painting is returning your gaze. You feel uncomfortable, try to change your position, but the eyes keep following you around the room. Can it be real?

We expect to contemplate art but can art contemplate the viewer?

The portrait genre was born out of a primal urge of conquering the biggest obstacle of life – namely death. In this monumental challenge, the artist’s work is similar to a true magician or to the old practice of an alchemist. Both the alchemist and the portrait artist set out to transfer the living object into tangible material whether a philosopher’s stone or paint. Curiously, a medieval artist’s studio would look no different from that of an alchemist: we would find rare minerals purchased from an apothecary (a modern day pharmacy), a grinding stone for mixing pigments or potions, various thinning agents, collections of curiosities from skull and bones to other natural wonders, an array of measuring tools such as compass, square, scale, a sand clock, and fascinating manuscripts full of peculiar designs and secret recipes.

The sensation that we feel of a real life presence in a work of art, as if confronting another human being, can be called an Alchemical portrait. This particular approach to portraiture aims at capturing the soul, the presence, and the breath of the subject in the fluidity of paint. It alters the fleeting into permanent and the invisible into visible. It surpasses the ordinary portrait which embellishes the truth resulting with a distorted image that flatters, aggrandizes, or presents an inflated identity.

Nearly 2000 years ago, we can find this approach in Egyptian Fayum portraits. They stare at us as fresh as the day they were painted. The Romans didn’t just call-in a priest or a doctor when it was time to move to the next world – they summoned the artist. Based on ancient Egyptian beliefs, the Romans anticipated the crucial moment when the soul was about to leave the person. In this magical instant, if the soul would recognize itself as if in a mirror in a life-like portrait, it would transfer straight into the work of art. If not, the soul would be lost forever. The portrait was a kind of soul-catcher and was eventually placed directly on the face of the mummified body. The painting thus literally took over the model, or the two became one: the subject was now dead but the painting would come alive.

From the biblical account of Veronica Veil of the magical portrait of Christ to the impulse behind iconoclasm to assassinate representation as if it were an actual living person – the power of representation becomes evident.

I live this theory through my art. My painting begins from the impulse of transferring the presence of the subject into a living portrait however unflattering it may seem. It is based on a series of reflections; a collaboration between the model, artist, and the viewer. The artwork acts as a connecting agent in time and space. The artist and the model can be long gone, but the conversation between the painting and the viewer continues.

“He went up to the portrait again, so as to study those wondrous eyes, and noticed with horror that they were indeed staring at him. This was no longer a copy from nature, this was the strange aliveness that would radiate from the face of a dead.” Nikolai Gogol, The Portrait, 1835

Visit the paintings in this article in a premier exhibition Larger Than Life, on view October 25th – November 29, 2014 at Hinge Modern in Los Angeles.