Sage: The Forgotten Healer

By F.R.E.E. Will LuxEco Editorial Assistant & Author of In the Spice Cabinet

By F.R.E.E. Will LuxEco Editorial Assistant & Author of In the Spice Cabinet

The holiday season is once again in full swing and I’m sure everyone is still going through their fair share of leftovers—which in my opinion are just as hearty on the days following Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Years as they are the day of. It is in that same vein of heartiness that I talk about this next entry of this particular chronicle. While most are still reminiscing over the desserts and going for the last helping of sweet potatoes (myself included), allow me to direct your focus just a little to an herb that tends to get overlooked but plays just as important a role in the holiday festivities, and beyond.

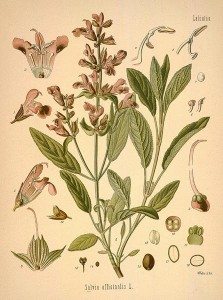

Anyone who has a family member that makes a good stuffing (especially oyster stuffing) or cooks a mean water fowl (i.e. duck, goose, etc.) would surely be familiar with the aromatic (but not the tastiest to some) flavor of sage. Unlike previous entries in the In the Spice Cabinet series, sage comes from the Mediterranean region all along the southern portion of the European continent and ranging all the across the Adriatic sea and into Asia Minor. With its unmistakably pungent aroma, bitter taste (almost acrid to some) and roughly textured yet feathery soft grey-green leaves (the underside being greyer than the tops and much softer), sage is one of those herbs with a history as robust as the flavor it imparts to your favorite savory dishes.

A member of the mint family, sage is an evergreen shrub that at one time was one of the most coveted herbs in the world. Its name is derived from the original Latin name, Salvia, which means to save. Most European dialects, especially in Western Europe, have a derivation of the Latin name. Also surprising are the similarities between the official Latin genus name, a number of dialects from the Baltic region (Croatian, Bulgarian, Czech, etc.), and even the Japanese and Korean translations (more on that later). Like with other spices I’ve researched there are numerous different species that fall under the genus Salvia all of which vary from the size and width of the leaves, to even their scent. The one of course everyone is familiar with is the common garden sage or Salvia Officinalis, of which there also many varieties depending on where on the European continent you find yourself.

From ancient times, to the Middle Ages, and up until the late 18th/early 19th Century sage was renowned more for its medicinal properties more than for its seasoning qualities. European nations like France and Portugal also have names for sage that denote its use as a tea that has been widely used throughout the centuries. One of the functions of this tea was to induce sweating when consumed hot and stop sweating when taken cold making it good for flu and cold-like afflictions. Ancient Greeks are reported to have used the herb more to combat digestive problems and has been proven to quell diarrhea and excessive gas making it a more than adequate carminative. Other reported benefits of drinking sage tea are the healing of ulcers (especially when mixed with lemon/lime and honey), the aiding of digestion and overall toning of the body’s digestive tract, and is helpful in soothing sore throats. When applied externally sage acts as an astringent due to its volatile oil content. This makes it useful in treating cuts and abrasions of various sizes, an effective poultice for achy joints/muscles and a suitable anti-venom for treating snake bites and scorpion stings. And of course one would be remiss when speaking of sage if they didn’t mention its ability to calm frayed nerves and facilitate more focused concentration and alertness.

So popular were the medicinal qualities of sage that in the 9th Century Emperor Charlemagne cultivated the plant in his own imperial gardens. Before orange pekoe and earl grey were the norm, tea brewed from the leaves of sage was what accompanied an English breakfast. For those with a stronger constitution and a taste for something with a little more kick, the leaves and seeds of the red-topped sage (Salvia Horminum) were added to fermenting vats to increase the inebriation factor to ales; and the Dutch used the leaves and flowers of the variety native to Holland (Salvia Glutinosa) when flavoring country wines. The Greek variety of sage (Salvia Pomifera) has a unique feature where it would produce ¾” thick galls when punctured by wasps similar to the way in which they appear on the branches of oak trees as well. These clear protuberances known as “sage apples,” contained tannins and were gathered, sweetened with sugar and made into a sweetmeat conserve which is a delicacy in the area. In establishing trade with the Western World the Chinese traded their finest tea with the Dutch at a rate four times the quantity of sage received in return. There the leaves were brewed as a tea and used as a yin tonic (as opposed to the yang qualities of ginger) used to stimulate the flow of bile and help detoxify the liver, and also stimulate the circulatory system. It was also used to help women with a variety of hormonal problems such as menstrual cramps, hot flashes and perspiration associated with menopause, and even to dry up excessive breast milk once the child has passed the age of weaning.

Around the 19th Century the idea of using such a versatile herb for seasoning food became the thing to do, especially amongst colonial settlers. Unfortunately as the use and discovery of other more subtle (read: milder) spices, sage slowly disappeared into obscurity as opposed to fell out of favor—it was to a lot of people an acquired taste to begin with. Those who did use sage in the kitchen noticed that the pungent aroma became a little more tolerable, even pleasant upon cooking it. A few dried, crushed leaves of sage mixed with rosemary and marjoram worked particularly well with fatty foods such as water fowl (duck, goose, etc.), game birds, and red meats like pork and beef, veal especially, making them easier to digest because of the penetrating oils absorbed best by the fat. Sage also tends to compliment a variety of vegetable dishes as well including eggplant, lentils, soups and stews, or even something basic like carrots or string beans. Because of its potency it is best to use only a few fresh leaves in cooking as too many can easily overpower the most aromatic of dishes. A few shakes of powdered sage would also be just as effective. It also lessened the less than pleasant aftertaste associated with onions and garlic which could explain to this day why sage is a common ingredient in the stuffing we consume during the holidays.

Around the 19th Century the idea of using such a versatile herb for seasoning food became the thing to do, especially amongst colonial settlers. Unfortunately as the use and discovery of other more subtle (read: milder) spices, sage slowly disappeared into obscurity as opposed to fell out of favor—it was to a lot of people an acquired taste to begin with. Those who did use sage in the kitchen noticed that the pungent aroma became a little more tolerable, even pleasant upon cooking it. A few dried, crushed leaves of sage mixed with rosemary and marjoram worked particularly well with fatty foods such as water fowl (duck, goose, etc.), game birds, and red meats like pork and beef, veal especially, making them easier to digest because of the penetrating oils absorbed best by the fat. Sage also tends to compliment a variety of vegetable dishes as well including eggplant, lentils, soups and stews, or even something basic like carrots or string beans. Because of its potency it is best to use only a few fresh leaves in cooking as too many can easily overpower the most aromatic of dishes. A few shakes of powdered sage would also be just as effective. It also lessened the less than pleasant aftertaste associated with onions and garlic which could explain to this day why sage is a common ingredient in the stuffing we consume during the holidays.

Coincidentally sage is one of the few herbs that are able to retain much of its volatile oil content when dried and crushed making it invaluable as an ingredient in dry rubs and marinades. The volatile oil (or essential oil) that comes from sage contains a compound called thujone which makes up anywhere from 35-60% of the essential oil depending on the type of garden sage used. This particular compound is the reason behind sage’s ability to inhibit the flow of sweat and other bodily fluids, and is also known to have anti-putrefying effects making it excellent as a natural preservative of meats and cheeses (a bonus effect next to the flavor imparted). Thujone has also been documented to have a hallucinogenic effect if taken in large quantities over long periods of time. Other compounds contained in the essential oil include rosmarinic acid (which when absorbed into the body has anti-spasmodic and anti-inflammatory properties), camphor elements, and pinene; all of which contribute to the overall effectiveness of sage when using it for various afflictions. It’s the compound thujone however that determines the best quality of sage which today, as it was hundreds of years ago, comes from the mountainous region of Dalmatia and Croatia. There within the mountain range lie vast fields of wild sage which is harvested 3 times a year by the inhabitants of the region and has been a cottage industry for years.

It is also of note that there are cultivators of sage who are native to the North American continent. While most are strictly for ornamental purposes, there are a few worth mentioning. Those with more spiritual leanings are probably quite familiar with the variety of white sage (Salvia Apiana). To this day Native Americans from Meso-America all the way up to the Southwestern United States used this sage in lotions and salves for cuts and skin eruptions and the leaves were also chewed to alleviate gum pain, toothaches, and were also used as a natural toothbrush. It was also used in sweat lodge purifications to induce sweating, purifying the body; burned as incense to purify the air or space in preparation for ritual ceremonies, and ward off less than desirable spirits. As a hot water infusion, white sage and also garden sage were used as a natural hair treatment for those of us with gray hairs.

Unfortunately due to the popularity of these smudge sticks, many people have taken it upon themselves to trek to the California desert countryside and unceremoniously harvest these beautiful plants from their natural habitat and proceed to dry and sell them without regard for sustainability and disturbing an already delicate ecosystem contributing to erosion and removing a vital pollinating plant for bees and hummingbirds. For those dying to have their own white sage to dry and use for smudging, it can be obtained from more reputable places either online or at your local metaphysical shop. Or of course you can check for its availability at your local nursery. The other variety of sage from North America worth mentioning is Salvia Columbariae or Chia sage. The seeds of this particular North American Sage were considered highly nutritious by Native Americans and are still sold to this day at health food stores (usually on the same aisle as flax seed) as a snack rich in antioxidants and essential fatty acids that can be eaten by itself or added to baked goods.

Today sage has found its way back into the forefront of herbal health, and preventive medicine. In Japan, studies have been conducted to determine whether sage’s calming effect on the nervous system and stimulation of the circulatory system can assist in preventing blood clots which can lead to other ailments of the heart. Other studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of sage against more serious neural disorders like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, and it’s anti-fungal properties have been looked at as a means of combating overabundance of candida albicans (yeast infection) while still maintaining the appropriate balance of useful bacteria the body needs to function properly. Elements of the volatile oil extracted can also be found in some toothpastes and mouthwash products.

The story of sage is truly one that has come full circle. From being a prized herb for its healing and cosmetic qualities, to a useful culinary seasoning, to being relegated to holiday cuisine, then fading into obscurity only to be brought back to the forefront of alternative medicine. While doing research for this article I came across a myriad of quotes heaping praises upon the healing power of sage (most if not all of it well due); but one in particular caught my eye and ironically enough was one of the first quotes I came across, giving me enough time for the words to resonate enough for me to truly comprehend their relevance. Translated from its original Latin text the quote reads: Why should a man die whilst sage grows in his garden? This not only speaks to the efficacy of sage but also the plant’s hardiness, being able to withstand everything but the harshest droughts and coldest of winter storms. So when you got to lay out that plot for your garden, be sure there’s enough room for your own sage. You never know when you might need, or when it might come in handy—regardless of the season. Until next time, have a happy holidays whatever you celebrate, and a very blessed and peaceful new year to one and all.

I have fun with, cause I found just what I used to be having a look for. You have ended my 4 day lengthy hunt! God Bless you man. Have a nice day. Bye